Q+A with Jennifer Sonderby, former Design Director at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Lonny Israel, head of graphics at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

The expanded logo becomes a portal in which to enter the museum at the Third Street entrance. ©Henrik Kam 2017

During the recent transformation of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)’s building, with an expansion designed by the architecture firm Snøhetta, the museum embarked on a profound reexamination of its values, its experience principles, and its relationship to its audiences. The exhibition program was expanded and changed, the brand repositioned, and the visual identity reimagined.

As part of this effort, the museum extended its newly conceived visual identity into a cohesive wayfinding and environmental graphics system that, like the new building and the visual identity, is designed to be open and welcoming and to enhance the museum experience.

Extending throughout the 460,000 sq. ft. of the museum, the wayfinding project included over 1500 individual signs, as well as three large-scale exterior signs. The signage system was designed to welcome over 1.25 million visitors to explore art, while covering the needs of building code requirements, donor recognition and onsite marketing.

In the Q + A below, Jennifer Sonderby, former SFMOMA Design Director and lead on the Building Identification and Wayfinding project, and Lonny Israel, head of the graphics team at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, the consultant Jennifer hired to partner with SFMOMA on the project, discuss some of the details.

The redesign of the SFMOMA visual identity—like the building expansion itself—was a large scale and ambitious undertaking. With your design team at SFMOMA working on the core identity, when did you identify the need to bring in a consultant to help with the environmental signage? What factors did you consider in choosing the design department at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP (SOM)?

Jennifer Sonderby (JS): Because of the construction timeline, the museum considered options for this component of the project four years before the museum reopened and a full 18 months before we had the logo finalized. We were looking for a team that was comfortable with working without assets until much later in the process—and one that shared a similar design aesthetic and enjoyed close collaboration.

What served as inspiration for the design of the wayfinding? How did the design of the wayfinding relate to the other initiatives that the museum was pursuing?

JS: The goal of the museum through the expansion project was to connect more broadly to our community, welcoming more people than ever before to explore the possibilities of art. This meant opening up and becoming more relatable. “Welcoming” and “open” served as guiding principles that inspired not just the new visual identity but all other components of the museum experience—from virtual spaces such as the website to the physical signage.

The new SFMOMA logo is designed to contract and expand, allowing it to become a conceptual frame in which to view content.

To ensure that the visitor was at the center of decision-making as we embarked on major initiatives such as wayfinding, a cross-functional internal team called the Visitor Experience Task Force met weekly to discuss all aspects of the new experience of the museum.

One result of this team’s work was the development of a visitor experience journey map and a set of priorities that served as tools to guide the process.

The ethos of the brand was extended into every aspect of the experience —even into the design of the icons for the restrooms.

Wayfinding icons were developed specifically for the project using the SFMOMA typeface as a basis. The icon set includes a non-traditional representation of a family for its Family Bathroom sign in order to reflect the progressive mindset of the Bay Area while reinforcing the values of the institution. Photo: ©Henrik Kam 2017

Rather than represent “family” with an icon of a mother, father, and child, the SFMOMA family restroom symbol includes figures of two moms, two dads and a child—a progressive family that reflects the values and welcoming mindset of the institution and the Bay Area.

The museum’s “wheelhouse” includes bike parking for the staff. Photo: ©Henrik Kam 2017

One of my favorite signs is the one for the staff bicycle storage room. Located adjacent to the museum offices entrance, the nomenclature takes a lighthearted approach, inviting staff into the “Wheelhouse.”

Lonny Israel (LI): Our team was inspired by the architecture of the building—both the original building by Mario Botta and the expansion by Snøhetta. We wanted to develop a unifying voice that would run as a thread throughout the museum and, as Jennifer mentioned, to ensure that the design embodied SFMOMA’s unique spirit. A goal of the wayfinding graphics was to activate the new identity elements in a way that would convey a welcoming sense to visitors as well as the other experience principles Jennifer noted.

What was the collaboration process like?

LI: We always look forward to the opportunity to collaborate with the client and partnering firms, and this instance with SFMOMA and Snøhetta was no different. The project schedule was already established and so it guided the process. Our team figured out the framework for the signage package well ahead of time, not knowing what the identity elements were going to be. We developed placeholders and designs for all of the signage in order to identify areas of integration with the architecture, and to obtain pricing. And there was an extensive mock-up phase, with full-size prints pinned up on-site, both as a tool for fine tuning the messages and graphics, and to get final design buy-in from the stakeholder group.

Paper mock ups of the signs were reviewed during construction to test and fine tune the wayfinding strategy.

JS: It was a very fluid process. Since the research and planning phase of the signage occurred at the same time as the development of the visual identity, we shared ideas along the way which allowed the design of the identity to respond to our more complex platform challenges such as signage.

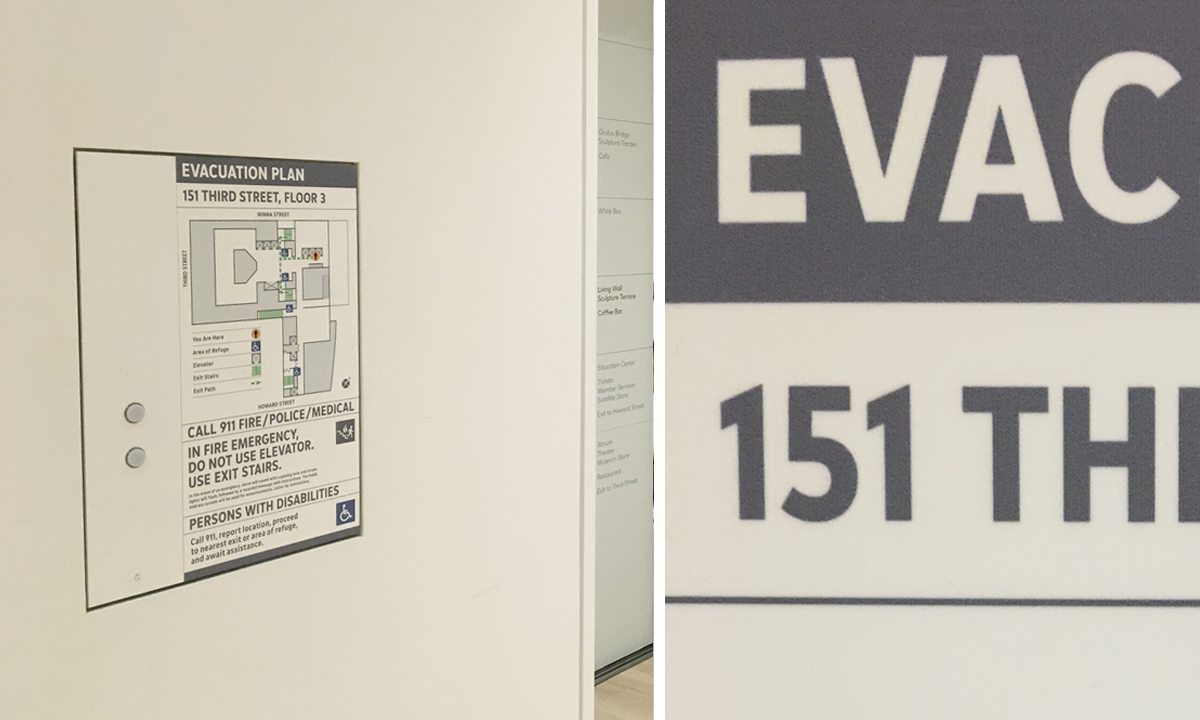

This back and forth was particularly effective during the development of the museum’s custom typeface. In addition to designing SFMOMA Display and SFMOMA Text, a condensed version was designed according to the requirements specified by San Francisco code for use exclusively on the museum’s evacuation maps. This meant we were able to have typographic consistency throughout every facet of the project, even on these highly restrictive and functional signs.

SFMOMA’s custom typeface was designed to match the letters in the SFMOMA logo as well as cover a wide range of specific needs—from large display signage to running text in catalogues to use in digital platforms.

A condensed heavy weight version of the SFMOMA typeface was designed according to building code requirements for exclusive use on evacuation maps.

How does the signage system respond or not respond to the different architectural styles of the Mario Botta and Snøhetta designed buildings? What are some of the challenges in seaming together two architecturally different buildings?

LI: I think Jennifer would agree that in some ways the architecture is a study in contrasts. There are the grounded qualities of the Botta building compared to the ethereality and lightness of the Snøhetta building, and so the signage program needed to strike a visual balance and not align itself to one or the other. To use the consistent visual expression of SFMOMA through these graphics to help visitors find their way through the museum, creates the appropriate seam, making the two works of architecture into one institution.

JS: Exactly. We looked for ways to seam the buildings on the exterior as well. For the first time in the institution’s history, prominent building identification was placed on the exterior of the building—a large warm red logo positioned on the exterior of the white clad Snøhetta designed building and a white logo placed on the warm red brick of the Mario Botta designed building.

The color of these identifiers, alternating between red and white and placed at the same hang height, serves to visually unify the two architecturally distinctive buildings. The south west corner of Howard and Third street is the ideal spot to view the two buildings, and to Lonny’s point, really observe their inherent contrasting qualities that our design was meant to acknowledge and complement.

Large scale building identification signage was installed for the first time on the exterior of the museum at both public entrances. Photos: left: ©Snohetta; right: © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

The installation of the letter “M” on the façade facing Howard Street . Photo: ©Jennifer Sonderby

Inside, the elevators proved to be a surprising challenge. The joining of the two buildings created a condition in which two sets of elevators, one set in the Botta building and one new set in the Snøhetta building, are located on the same wall but they access different sets of floors. The existing Botta elevators travel to floors 1-5 while the new Snøhetta elevators carry visitors to the upper reaches of the new building, from floor 2 to floor 7. To avoid confusion, we painted the elevator doors—red in the Botta building and silver in the new Snøhetta building--and then applied large scale typographic directories to the front of the elevator doors so that when they’re closed visitors can clearly understand which floors they can access.

The “Red Elevators” with directories applied to the front of each set of doors allows visitors to quickly understand which floors the elevator accesses and consider their art viewing options while they wait. Photo: ©Henrik Kam 2017

What were the challenges in balancing the functional needs of the signage with the aesthetic sensitivities found within a modern and contemporary art museum?

JS: Our goal with the signage was to provide just enough guidance to our visitors so that they felt comfortable to wander without the fear of getting lost. This meant fine tuning the strategy and minimizing the visual footprint as much as possible without compromising legibility or the functional needs of the signs.

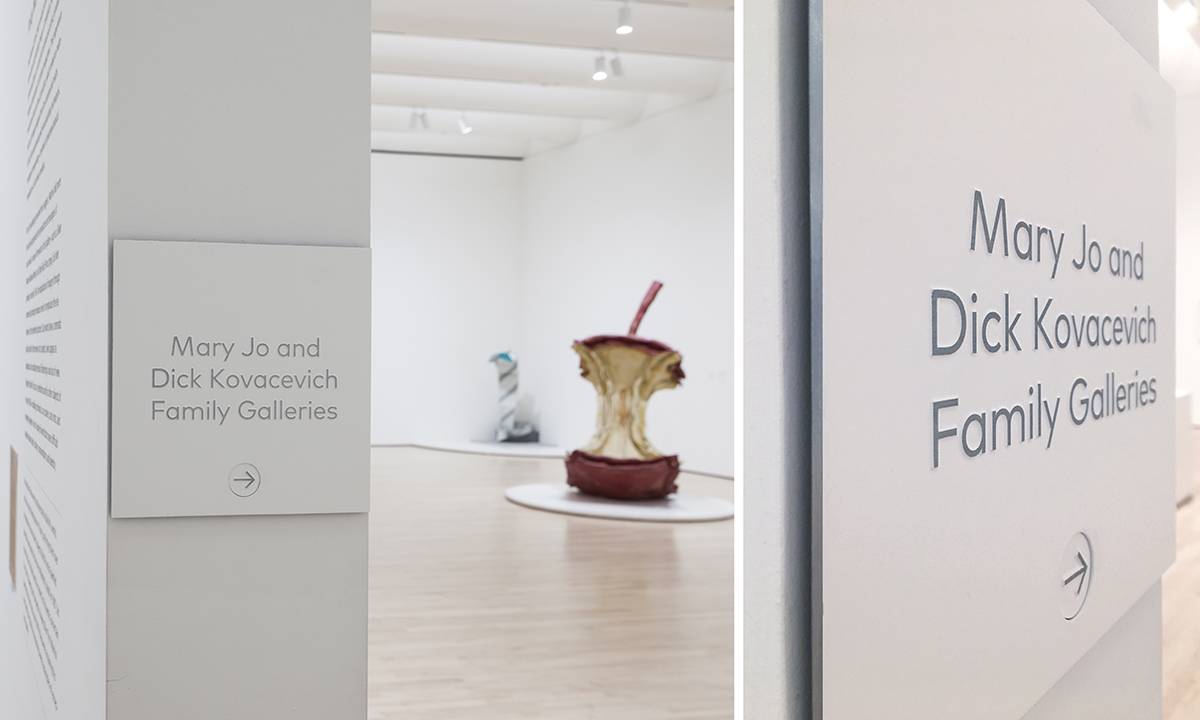

With this in mind, we developed two types of signs to acknowledge the various donor contributions: pin-mounted letters that appear on the landings, and donor plaques for individual galleries. This two level strategy minimizes the visual distractions within the galleries. Given the range and generosity of donor contributions to the museum, this modest two-level strategy was an exceptional feat.

In addition, a cool grey and white color palette used throughout the interior architectural signage allows the artwork on view to take center stage—and visitors to get lost in the art, but not the building.

The individual gallery donor plaques include repositionable arrows that allow the signs to be seamlessly relocated within the gallery thresholds. Since the gallery walls are often reconfigured, this was a critical design consideration

LI: In addition to the thinking behind the design, there was a large stakeholder group that provided input. From the beginning of the project, all the various stakeholders recognized the importance of having a signage program that was visible and welcoming. Through discussions, drawings, mock-ups and many walks through the site, sensitive locations were identified and resolved successfully without compromising the art experience, the architecture or the wayfinding program.

The materials used throughout the architectural signage are, for the most part, structurally non-invasive—applied directly to the wall in vinyl or atop glass. Was it important to respect the physical integrity of the building and not add structural layers into the wayfinding system?

JS: The core set of wayfinding signs were set in vinyl so we could easily make adjustments once we learned more about the building and its visitor circulation after the museum reopened.

LI: And we were interested in creating a system that allowed maximum flexibility and was cost effective, but more importantly a system that had a light touch—one that did not add extraneous material which would only serve to cover or hide the architecture. We liked the feeling that the architecture and the messaging were integrated as one.

SFMOMA put aside a reserve to be used at the end of the project that would allow the graphics and wayfinding to be evaluated and fine tuned (after approximately six months). This post-occupancy evaluation is not commonplace for our projects, so this was definitely a plus. It’s valuable because the needs of users and visitors are rarely fully anticipated in the beginning.

The two most visible signage systems within the museum include the environmental signage which is quiet and the exhibition graphics system which is louder—using color, images and expressive typography. Were there any considerations made to the architectural signage to take into account the proximities of the two systems?

JS: Given the frequent changes to the exhibition graphics on the title walls and throughout the galleries, the wayfinding and donor signage had to have a quiet but confident visual approach—one that could hold its own on a landing wall with floor to ceiling expressive typography and large scale visual graphics. The two systems were designed to dialogue with one another—politely.

A example of a typical exhibition title wall that includes a museum directory, pin mounted donor signage and exhibition signage—in this case, for “Open Ended: Painting and Sculpture since 1900”. Photo: ©Henrik Kam 2017

JS: To allow efficient means in which to repaint the exhibition landing walls, the pin-mounted donor signage which appear on each of these walls, were designed to easily slide in and out of metal sleeves that are embedded into the walls. This was an important consideration given that the exhibition landing walls in which these signs appear are repainted frequently.

The pin-mounted donor letters are easily installed and de-installed on exhibition title walls through the use of metal sleeves that are permanently embedded in the wall. Photo: ©Henrik Kam 2017

What were the overall considerations for integration of digital signs into the signage system?

JS: Since the first and second floors of the museum are designed to welcome visitors, it made sense that the digital screens serving up information about the programming throughout the museum would be placed here.

We restricted the use of screens to these locations, choosing not to include them on elevator landings throughout the upper floors of the museum in order to minimize distraction from the art on view. Even the elevator landings on these floors are considered gallery space and include artworks.

For SOM, compared to other signage projects, what made this one different than other projects?

LI: This is the first time we were hired by a client who is also a graphic designer. This was a highly visual stakeholder group that continually challenged us. Discussion was lively, highly detailed and made for a stronger project. Designing an appropriate signage and wayfinding program for such an important institution, one that would serve to unify two highly prominent works of architecture, made this project uniquely rewarding.

How was the signage received by visitors, curators and frontline staff of the museum? What, if any, tweaks will be made to the system in response to feedback?

JS: The physical signage is only one part of a larger wayfinding system that includes staff, printed maps and other visual cues to help visitors to move confidently thorugh the museum. Based on visitor surveys in spring 2017 conducted by Morris Hargreaves McIntyre (MHM), an audience research agency specializing in the cultural arts, the signage system scored 8 out of 10—which according to Andrew McIntyre, principal at MHM, is “exceptional” for a new building project.

Aside from the physical signage, another key component of the wayfinding strategy is the front line staff. Warm red t-shirts were designed to help visitors quickly identify museum staff.

The changes thus far to the system have been minor “fine tuning” tweaks rather than extensive revisions. Having spoken to several peer institutions who have expanded or opened new spaces, we know we are an anomaly in this respect—and this is a good thing.

For more information about SFMOMA’s transformation, please visit:

New Visual Identity Introduced as Part of SFMOMA Transformation

Expand and Contract: Designing the New SFMOMA.org

Design Team

SFMOMA Design Team:

Jennifer Sonderby, Design and Project Lead

Bosco Hernandez, Designer

James Provenza, Designer

Carrie Taffel: Lead Project Coordinator

Nicole Sorci: Project Coordinator

SOM Design Team:

Lonny Israel, Lead Designer

Dan Maxfield, Designer

Brad Thomas, Designer

Pauline Cheng, Designer

Nathan Bluestone, Designer

Nick Gerstner, Project Manager